|

Lancastria enters the war

On the 16th of April she sailed to Glasgow before heading to Reykjavik, Iceland to pick up Canadian troops. On returning from Iceland Lancastria received orders to head to Norway. Churchill, as First Lord of the Admiralty masterminded the Norway campaign, a campaign that proved to be a disaster. No sooner had British Commonwealth troops been landed, than plans were being put in place for their immediate and sudden withdrawal as German forces overran the country.

Lancastria left Glasgow at midnight on the 28th of May and arrived at her anchorage in Norway at 3.00am on the 4th of June. There were over twenty liners converted into to troopships manoeuvring in the cold waters off Namsos. The accompanying destroyers did the tough job of running into the mainland and bringing off the soldiers. Canadians, Poles, French and British troops, many nationalities, all dirty and depressed and most without rifles. 2653 troops were taken on board Lancastria in difficult sea conditions. Lancastria averaged 14 1/2 knots on her return journey. On the 8th of June Lancastria arrived in Scapa Flow and off loaded some of the troops who were sent to a "secret" camp on the hill above the small Orkney town of Stromness. Large Hessian sheeting was arranged around the perimeter of the camp to prevent locals from witnessing the scale of the Norway evacuation. The next day Lancastria headed for Greenock in order to off load more troops.

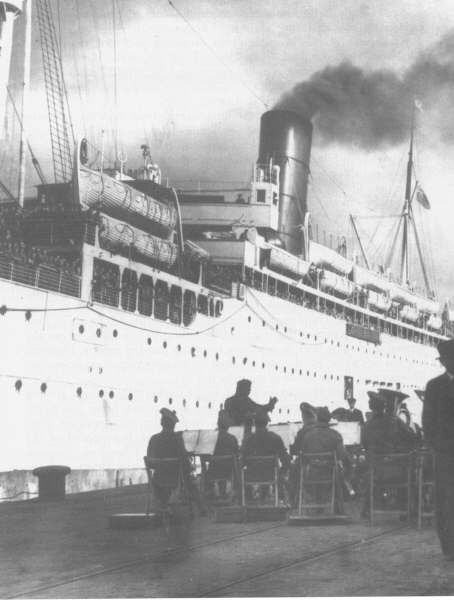

< Lancastria at Greenock a few weeks before being sunk

During that return trip she came under attack by highflying aircraft that dropped two bombs. Both missed and no damage was done. At Greenock she loaded some 55 tons of oil fuel before being sent to Liverpool for overhauling and dry-docking, arriving on the 14th of June. Secrecy, as with all earlier military operations in which the Lancastria was involved, meant that neither the crew, nor the Captain himself, knew where the next destination would be. That being the case, Lancastria was always fuelled and supplies loaded to their maximum to cover all eventualities.

To Lancastria's Chief Officer, Harry Grattidge, it had seemed a relief at the time. Lancastria's crew needed a break as much as the liner needed its overhaul. In the first months of the war the losses in the Merchant Service was greater than in all other British services put together. Tension amongst the crew slackened greatly as they entered Liverpool. At 11.00am the crew were paid off. As the vessel was prepared for dry-docking in Liverpool's Gladstone Dock, Grattidge went for lunch at the Adelphi, then strolled down to the Cunard Offices at Pier Head to pick up his rail voucher. Grattidge had planned to take three weeks leave in the Lake District.

Captain Sharp, Lancastria's Master. Sharp survived the sinking and went on to Captain the Laconia which was torpedoed and sunk on 12th September 1942. Sharp, realising the vessel would sink and perhaps not able to take the loss of another of his ships, reportedly locked himself in his cabin and sank with around 1600 other victims. Captain Sharp, Lancastria's Master. Sharp survived the sinking and went on to Captain the Laconia which was torpedoed and sunk on 12th September 1942. Sharp, realising the vessel would sink and perhaps not able to take the loss of another of his ships, reportedly locked himself in his cabin and sank with around 1600 other victims.

As soon as Grattidge entered the office he knew something was wrong. Cunard's Marine Superintendent Captain Davies was relieved to see Grattidge. The little Welshman said to Gratidge:

"Thank God you're here, big trouble. Grab a taxi now and get to the ship and recall everyone. You haven't much time - you're sailing at midnight. The mission is urgent but unspecified. The ship's needed in Plymouth."

Grattidge returned to the ship and gave orders to Chief Engineer Dunbar to get steam up. He telephoned Captain Sharp telling him of the situation. Over the next few hours Grattidge busied himself sending out telegrams and arranging for the recall to be broadcast at railway terminals. Loudspeakers at Central and Lime Street stations boomed out across the crowded platforms.

"Any present or recent members of the crew of the Lancastria are requested to report to the station master's office at once."

All but three of the crew made the call and that night the Lancastria left Liverpool for the last time. The crew ranged in age from 14 year old Tom O'Conner making his first voyage as a deck boy to Don Sutherland who was aged 74.

Lancastria had left Liverpool hundreds of times before, taking with her thousands of holidaymakers and immigrants setting out for a new life and hopefully greater prosperity. Normally hundreds crowded the deck rails waving handkerchiefs to the crowds assembled on shore. Lancastria's siren high up on her huge single funnel blew one long blast before the vessel increased speed, her bows slicing evenly through the water.

|

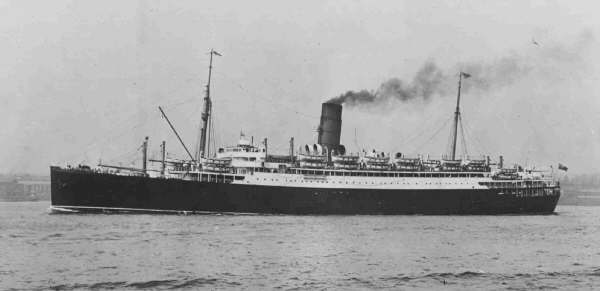

Lancastria departs from Liverpool in peacetime

Late on the 14th of June she departed in silence and in darkness. None of those on board knew her final destination. No provision was made to off-load some of the fuel oil taken aboard Lancastria. The liner had two deep oil tanks, each capable of holding 1500 tons of oil. On Sunday morning at 07:00hrs, 16th June 1940, Lancastria dropped anchor off Plymouth.

Neither Captain Sharp nor Grattidge ventured ashore at Plymouth but before long Ministry of Shipping officials had boarded and examined the troop accommodation.

That evening they left Plymouth for Brest along with another Cunarder and Clyde built liner the 20,341-ton Franconia. Franconia had been the flagship on the earlier voyages to Norway. The voyage to the French coast was uneventful but as soon as the sun began to break over the horizon a different scene could be viewed unravelling. The crew could see nothing of Brest or indeed the adjoining coastline, due to vast columns of thick black smoke caused by demolition teams destroying the last of the oil dumps. The smoke was too heavy to be broken up by the light breeze. Captain Sharp looked at Chief Officer Grattidge and said,

"It's no good going in there. The place is done for. We're too late."

An accompanying destroyer, possibly HMS Highlander, signalled to Lancastria to proceed to Quiberon Bay and so the two great liners sailed South on that Sunday afternoon, in sight of the French coastline.

At around eight o'clock in the evening they neared their destination. The Lancastria was some way astern of the Franconia. As the larger vessel passed through the first of the boom defences, in place to prevent attack by U-boat, an enemy aircraft dived out of the dark sky. Four bombs fell into the water between the Franconia and Lancastria. As the aircraft levelled out it strafed both ships with machine gun fire.

Lancastria's carpenter, Fred Bradley was stationed by the windlass on the fore deck when the attack took place. He was perhaps the only member of crew to witness the whole thing and saw the entire stern of the Franconia lift clean out of the water by one of the exploding bombs.

Although none of the bombs actually hit either vessel the proximity of the explosions to the Franconia shattered and sprung her plates and put out of action one of her engines. Franconia's Master had no option but to drop anchor and tend to the ship's wounds. As Lancastria steamed past the crippled vessel and into Quiberon Bay to await orders the Franconia signalled "Good luck".

Shortly after Lancastria dropped anchor, a French trawler came alongside and notified Captain Sharp that the Bay was not safe and advised him that he should make for St. Nazaire. Sharp took the advice and within a short period was underway, alone, heading to the mouth of the Loire River and St. Nazaire.

Lancastria drops anchor:

In the early hours of Monday, the 17th of June 1940 the Lancastria eased her way towards the coast of France, a few miles from the port of St. Nazaire, escorted by a French pilot boat. One of its crewmen boarded Lancastria and made his way to the bridge where he advised Captain Sharp in perfect English that it would be wiser not to continue. He warned Sharp that anchoring the Lancastria so close to shore would be like putting "your head into a noose... when they see you anchored outside, a sitting target..."

Sharp shrugged his shoulders. "What alternative have I got?"

The day before another British merchant ship, The SS Wellington Star was sunk in the Bay of Biscay by U-101.

|