The 17th June 1940 - The loading begins

Lancastria dropped anchor around six in the morning, approximately three miles from the coast and in 72 feet of water. The area is known as the Carpenter Sea Roads. Her draft would not allow her to proceed any further and the French coastline was only faintly visible. 150 miles East, Nazi Germany's entire 31st Infantry Division was crossing the Loire River at Orleans. In front of it were the remnants of the British Expeditionary Force, more than 150,000 men. However unlike many of the units that managed to escape through Dunkirk two weeks earlier, the remaining troops were generally support and logistical units with little or no combat experience. During the six week German offensive which they codenamed "case yellow" the British Army had been completely routed by the faster and better equipped Germans who had spent years preparing for this invasion.

For the Lancastria it was a cool and brightening start to the day. Lancastria's crew could not hear the gunfire of the advance units of the German army, which were only 25 miles from the port of St. Nazaire. For the last few months Fifth Column units had been active in the region, known to the British forces as "Number 2 base, Sub-area, Nantes".

As Lancastria's anchor splashed into the brown, silt-laden waters only one other vessel was visible, the hospital ship, Somersetshire. She had lain there all night receiving evacuated patients from Number 4 Army Hospital. As daylight shimmered over the still sea the Somersetshire got underway.

The fateful order:

Suddenly three Royal Naval Volunteer Reserve (RNVR) Transport Officers appeared on the Lancastria's bridge. One of them, a Naval Lieutenant, approached Captain Sharp.

"How many can you hold?" asked the fresh-faced Officer.

"About three thousand, at a pinch." replied Sharp.

"You'll have to take as many as you possibly can, without regard to the limits of International Law." came the reply.

Chief Officer Grattidge realised the magnitude of this order and what dangers it represented. They were being asked to embark as many men as possible. They had lifeboats and life jackets for 2,200 people. Chief Officer Grattidge looked at the Naval Officer and said:

"What's going on? Is this capitulation?"

"Good God! Don't say that!" protested one of the Reserve Officers, and at that they left. There was no time to question the order.

Grattidge quickly rehearsed a boat drill and between seven and eight o'clock in the morning the first boats had started to make their way out to the Lancastria. Every inch of the boats making their way out to the Lancastria were crammed full of troops. One of the first and largest units to come alongside the liner belonged to the RAF, numbering two hundred men and eight officers. Wing Commander Douglas Macfadyen was in charge and shown to a cabin.

His contingent was led into Numbers 1 and 2 holds. Subsequent RAF units, mainly ground crew from 73 Squadron, were directed towards these two holds and by mid-afternoon Number 2 hold had more than 800 RAF service personnel crowded inside.

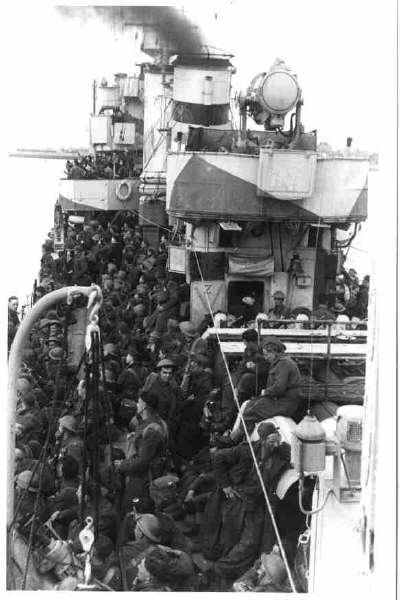

Troops aboard HMS Highlander en route to Lancastria

This was the very bowel of the ship. Great warehouses, lit only by dim electric light bulbs, set flush into the walls and surrounded by thick glass covers. Mattresses and palisades lay all over the floor space and effectively formed a thick carpet. One of the men, Leading Aircraftsman Ivor Jenkins shivered, "It's like a ruddy morgue", and risking a possible court martial decided to make his way to more 'homely' surroundings.

As more RAF personnel boarded some made their way down to "D" deck only to find it already fully occupied.

Captain Griggs of the Royal Armoured Medical Corps was seconded as the ship's adjutant. He had boarded at eight o'clock and along with Colonel Wilson of the R.A.M.C. were provided an office and started to get some organisation in place by collecting a nominal roll and visiting every part of the ship to obtain from N.C.O's (Non-Commissioned Officers) or officers in charge details of their contingent.

Whilst the other ranks were directed to the ship's decks and holds the commissioned officers and senior N.C.O's were allotted cabins.

Chief Steward and Purser Fred Beattie moved swiftly with Captain Griggs on the nominal rolls but took little heed of the smaller units that were boarding from the variety of craft which was ferrying men out to the Lancastria. Fred Beattie would later that day earn himself the British Empire Medal for meritorious service.

As some of the N.C.O's boarded they were handed a small card like a bus ticket. One R.A.F. Sergeant Harry Strudwick was given a card on which was printed 'Cabin 118. B Deck.' After weaving his way through the maze of corridors and companionways he eventually found Cabin 118. Inside the three-berth room was packed eight senior N.C.O's. After a few moments a couple of the N.C.O's decided to make their way outside whilst the remaining two or three decided to take advantage of the wash basin for a much needed wash and shave. Sergeant Strudwick never saw his fellow passengers again. He never knew what became of them or ever learnt their names.

|