|

In July 1940 the story of one man’s heroism on the day Lancastria sank was highlighted in The Scotsman newspaper. The text of Father Charles McMenemy’s heroic effort is carried below. Father McMenemy passed away in 1976. - Additional photographs and background courtesy of Siobhan Daly and the Edmundian Association.

July 1940 - Courtesy of The Scotsman newspaper

SCOTTISH PRIEST'S HEROISM

ASSISTED SOLDIERS ON LANCASTRIA

The heroism of a Scottish Roman Catholic chaplain during the sinking of the Lancastria in mid-June was described yesterday by a fellow priest in London.

He is 35-year-old Father Charles McMenemy, who was for seven years curate at the Blessed Sacrament Church, West Islington, under Dean William Attree.

The Dean said to a reporter yesterday:

"Father McMenemy helped in getting the men onto the tugs and French lighters when the Lancastria was bombed and sunk off the coast of Brittany. He led men through the bottom of the ship to some kind of exit at the side about six feet above the water and made them remove their heavy clothing before they jumped. To one Sergeant Major who could not swim he gave his own lifebelt. The Sergeant Major was saved.

"Father McMenemy was one of four or five Catholic chaplains on board. He is a very strong swimmer and was picked up after three quarters of an hour in the water."

Son of Mrs McMenemy and of the late Mr Thomas McMenemy a Glasgow merchant, Father McMenemy was ordained at St. Edmund's College, Ware, 11 years ago. He was Chaplain to Wormwood Scrubs Prison for four years until his appointment as a chaplain to the forces. He is now with an anti-aircraft unit in Northern England.

Charles Edward McMenemy wrote the following letter from France, in World War II, to his sister Aileen and her husband Ernest.

Headquarters

12th A.A.Brigade

A.A.S.F.

B.E.F

November 16th 1939

Dear Aileen and Ernie

This, with reasonable luck, ought to reach you within four or five days, so I will wish you, Aileen, all good wishes for your birthday, and many happy returns of the day. I'm afraid I'm rather late in writing, but there has not been very much opportunity. First there was the long journey to get here, and now I find my day pretty well filled up. But I'd better start from the beginning. There was some delay in leaving England owing to getting our transport away before getting on board ourselves. Then when we arrived in France there was a long road journey, broken constantly for further instructions. Finally we reached our destination and we are now "somewhere". Just where I'm afraid I can't tell you for obvious reasons. All I can say is that things are very quiet. There has been practically nothing in the way of excitement.

We had a most wonderful journey through France. Scenery varied considerably, but everywhere we saw the really wonderful colouring of autumn. I don't know whether it is my imagination or not but everything seems much later here. It is still a joy to see the countryside. The weather has been very strange. At first it was horribly cold, then it started raining, and then there came a very warm period with lots of sunshine. Now, unfortunately, it has turned very cold again with continuous rain. There is also plenty of mud of a peculiarly sticky nature. Than goodness I bought some gum boots before leaving England.

My main job is a most peculiar one. I have men scattered all over the countryside. Three here, ten there, thirty in another place. As a result I am out every morning until the evening visiting them, arranging for them to get to mass - there we are fortunate for we use the French churches - and dealing with all the little problems that come into a chaplain's day. My "parish" is about a hundred miles long and eighty miles wide. The result is - I now drive a car. I began to learn about three weeks ago, and already I have covered great distances under my own steam! There have been no accidents yet, though occasionally I stop on the way up hills and going round corners!

There are other jobs which have fallen to my lot. I am doing the censoring of letter here at Headquarters and I am also looking after the Officer's Mess. I don't think I shall really develop into a first class housekeeper. Each morning is a horror. I arrange meals - and foods - in French is an absolute nightmare. My French at its best is sketchy. When technical terms creep in it's just hopeless! Still it's not bad fun.

Last week we succeeded in getting a wireless set, so now we listen in to England. This brings a little touch of home into our lives, and altogether we are not at all badly off. The only discomfort is the lack of news about things and people we know. There is an appalling delay in the arrival of letters from home. I had one from Fr. Altree which took just on three weeks to arrive, and one from Mother which took just over a week. Do write when you get this. I shall try to write regularly now that the "settling-in" stage has passed.

We are only a small part here. There is the Brigadier, an awfully decent fellow, the Brigade Major and the Staff Captain, both good fellows. These two and I are beginning to be called the Three Musketeers. There are two other officers also billeted with us - both sound lads.

Our billet is very comfortable. A large private house which has central heating and constant hot water, one does not appreciate that fully until one has sampled the mud of France. I got stuck in it the other day, and when I went in search of help - the first three Frenchmen I met were Poles - all my good French sentences so carefully prepared were quite wasted! To-day I quite frankly gave up. I set off this morning meaning to do a big round, but only managed two places. Then the rain got so thick and the roads so bad that I came back while I could.

This is a most scrappy letter, I'm afraid, but it really is awfully difficult to write coherently. I can't tell you where we are, or in what part of the country or anything or anything at all interesting. It is a perfect waste of splendid material! So I have just have to put down anything that comes into my head - after censoring it mentally first!

There have been one or two strange meetings. On my way through France I met Fr. Savage who lives next door to me in London and who was at school with me. I also met a man whom I last saw in Inverness three years ago, a young Airman to whom I taught Catechism ten years ago, and a lad who left St Edmund's in 1937. As time goes on I suppose I shall meet more.

I'm not going to ask you to send anything out to me. We get 50 cigarettes every week, and in any case they are very plentiful and very cheap. As for the other comforts of life - well I seem to have provided myself with them before starting. Literature is rather a problem, but we share what novels we have and there isn't a lot of time yet for reading.

Now I am really stuck for something to write about. I won't ask you any questions about London. You will probably give me all the news when you write.

Good-bye for the time being. My love to you both.

Your affectionate brother

Teddie

C.E.McMenemy

Born in 1904 Charles Edward was always know in the family as Teddie. He was quite young when he left the family home to study at St Edmund’s.

He was ordained at St Edmund’s College, Ware on June 29th, 1929.

Father Teddie served as an army chaplain during the Second World War. Soon after the outbreak of hostilities he was serving in the thick mud of France, thankful for his recent purchase of gumboots. He was not the prolific writer that his father was

His "parish" was spread along a front of about one hundred miles, and was eighty miles deep. Visiting his flock forced him to learn how to drive.

He was billeted in a large private house with central heating and hot and cold running water which he obviously appreciated against the backdrop of cold, wet mud

In 1940 the troop ship Lancastria was bombed and sunk. The newspapers of the time picked up the story.

Extract from William Hickey column in the "Daily Express" (Thursday, August 15th 1940):

Hero in Orders

- "Lists of those missing from the Lancastria have not yet been issued- 2 months after the sinking; I am sorry that I cannot check, from the War Office or the Red Cross, the name of the hero of the following episode, or if he survived.

- Miss J Harding of Bromley, Kent, tells me the story thus:-

- "... My brother, an RAF sergeant, was one of the airmen at the bottom of the ship when she was hit. The companionways were crammed with troops, and it seemed as though the men down below were doomed.

- A sergeant-major, my brother and several others standing together were approached by an Army chaplain, who quietly told them to put their faith in God and follow him. He led them through the bottom of the ship to some kind of exit in the side, about 6 ft. above the water. Then he made them remove their heavy clothing before they jumped."

- The sergeant-major could not swim, so the chaplain took off his own lifebelt and handed it to him with the words that he would not need it, for if God willed he could come through alive.

- They jumped, and that was the last my brother saw of the chaplain. The sergeant-major was rescued with my brother... My brother joins with me in the heartfelt prayer that the chaplain was among the rescued."

- Extract from William Hickey column in the "Daily Express" (Monday, August 19th 1940):

Hero Named

- The chaplain whose heroism aboard the sinking Lancastria I described the other day has been Identified.

- He is Fr. Charles McMenemy formerly Roman Catholic chaplain at Wormwood Scrubs prison.

- He is a fine athlete, a rugger-player and swimmer. The man he gave his lifebelt to was a non-swimmer. "I knew I should be good for an hour in the water," he says. A boat picked him up when he had been swimming for about three-quarters of an hour.

- He is now with an AA regiment in the North of England

After the war he continued his pastoral work. In 1946 he became parish priest at the Church of the English Martyrs at Wembley Park. It was a small parish and he built it up to the point that the old wooden church was no longer adequate for the needs of the rapidly growing community. In 1963 it was decided that a new church should be built, however it was 1969 before the construction started. On July 8th, 1970 the first Mass was concelebrated in the new Church by Father Teddie and all the priests who had been ordained with him at St Edmund’s College back in 1929. In May the following year Cardinal Heenan formerly opened and blessed the church.

Father McMenemy in 1921, as part of the St Edmunds first team

The years of hard work and worries of running a parish took their toll. Father Teddie was unwell. On January 21st 1976, he collapsed and died while going on holiday to Edinburgh. When the news reached London, the parish was stunned. His funeral was held at his parish, concelebrated by more than a dozen priests and with the church full to overflowing.

Geoffrey Bond in his book "Lancastria" writes of Father McMenemy:

Captain Charles McMenemy, an army padre aboard the Lancastria had a certain cherished possession which he had succeeded in carrying through the French campaign. It was with him in his cabin, two decks down and second from the barbers shop. This was a pale blue Li-Lo, the epitome of comfort on a summers afternoon, basking on the beach or floating leisurely across a private swimming pool. But it was not destined for any such use on that June day. At the hour when Kensington dowagers were beginning to think, not of war, but of their afternoon cups of tea the padre picked his Li-Lo off the cabin floor, where it had been laid in readiness for a nap after a much needed shave.

At first it felt as if a heavy gun in the stern had fired twice, but when a strong smell of explosive pervaded the cabin and the ship rolled clumsily it was apparent what had happened.

The padre made his way through the corridor. Here the situation was amazingly calm, in direct contrast to what was happening elsewhere at the time. About three hundred troops packed the alleyway. They were cool and unruffled, though every man must have realised the threat of those bone-shaking thuds. Marshalled by an officer the men filed quietly up a companionway and on to the deck; each one waiting his turn as if in a rush-hour bus queue.

Soon the corridor was almost clear. One soldier had become hysterical and been bundled into a cabin in order to stop the mental infection spreading and developing into a disastrous stampede. But the youth soon recovered and was helped by understanding companions up to the deck. On the way McMenemy saw two men without lifebelts. The padre himself had not claimed an ordinary issue one, for he was a strong swimmer and now as he saw the pair hesitating he crossed to speak to them.

'Can you chaps swim?' he asked. They glanced uneasily at the water and shook their heads. 'Take this then,' the padre held out the incongruous, pale blue Li-Lo. 'Get into the sea and climb on it. You'll be all right.'

'Oh thank you sir. But what about you?'

'Don’t worry about me. I'll be safe enough. If God wills many others will be too.'

In his quiet, sincere way he gave them a blessing, watched them go, then turned to move on along the crowded deck. McMenemy saw a strange sight. A solitary figure dressed in full service marching order was standing rigidly to attention in all that mob of jostling, half clad figures. The padre came up to the man and recognised him as a private in the Pioneer Corps. The soldier saluted and then his homely face broke into a broad grin, bewilderment giving way to confidence at sight of the officers cloth.

'Thank God you're here sir,' the voice was rich with the brogue of Southern Ireland. 'What shall I do now?'

McMenemy looked at the man, quite unable, despite a straight face, to keep his eyes from twinkling with amusement. 'Can you swim?' he asked for the second time in five minutes. The private nodded and his helmet tipped at a rakish angle over his freckled snub nose.

'Then get into the water and swim clear of the ship before she finally goes under, advised the padre, 'But if I were you I'd take my boots off first!'

The deck was ankle deep in water and listing badly to port. Padre McMenemy joined a member of the ships crew and another soldier in trying to free one of the rafts which was still secured. However the wooden structure was cluttered up with sundry equipment piled high upon it and this had to be slung off before the mooring ropes could be reached and loosened. Although the trio worked hard and fast the water was soon rippling over their hands, swelling the knots until they were impossible to unravel. The sailor was the first to go, making for the side and disappearing into the crowded sea. The other two exchanged a glance. There would be no getting the raft away now. The water had won. Together they walked to the side. There was no need to jump. They stepped over and began to swim. The padre survived.

later again in the book, no mention of Father McMenemy, but this extract reads:

"Four soldiers, each holding one corner of a pale-blue Li-Lo were paddling away nearby. On the inflated rubber cushion lay a wounded sergeant major. The dark stains on the pale-blue rubber were not those of oil."

There is another unnamed reference to a padre, which may or may not be Father McMenemy:

Company Quartermaster Sergeant Johnson, of 663 Artisan Works Company Royal Engineers had slid down the side of the Lancastria and was soon clinging to a baulk of timber, on the other end of which there chanced to be an army padre, still wearing his traditional dog-collar. The pair hung on, not speaking, and drifted with the tide, until a German plane swept low overhead, machine guns blazing.

The Chaplin ducked, then looked up, cursing quietly towards a rear gunner who was easily visible in his turret. 'You bastards!' the padre remarked with feeling. 'Thank God you're human, sir' Johnson said and, comrades in the face of adversity, they drifted on.

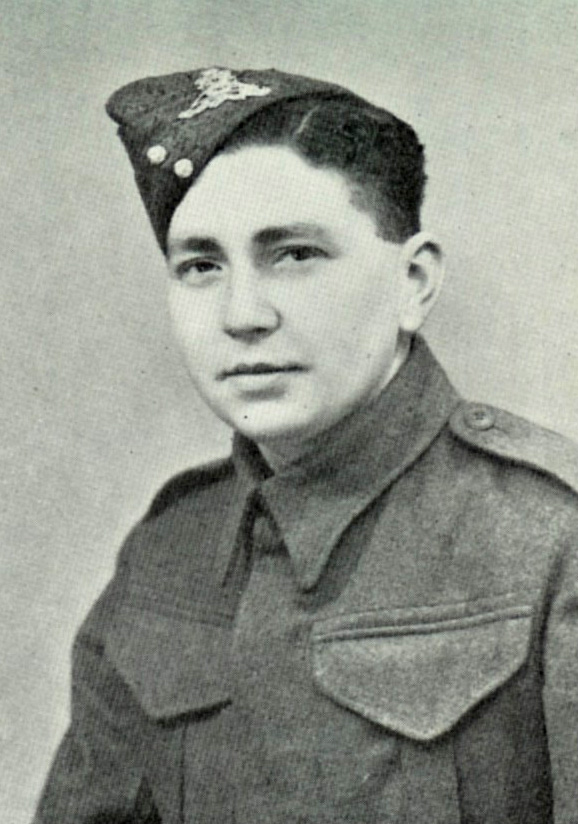

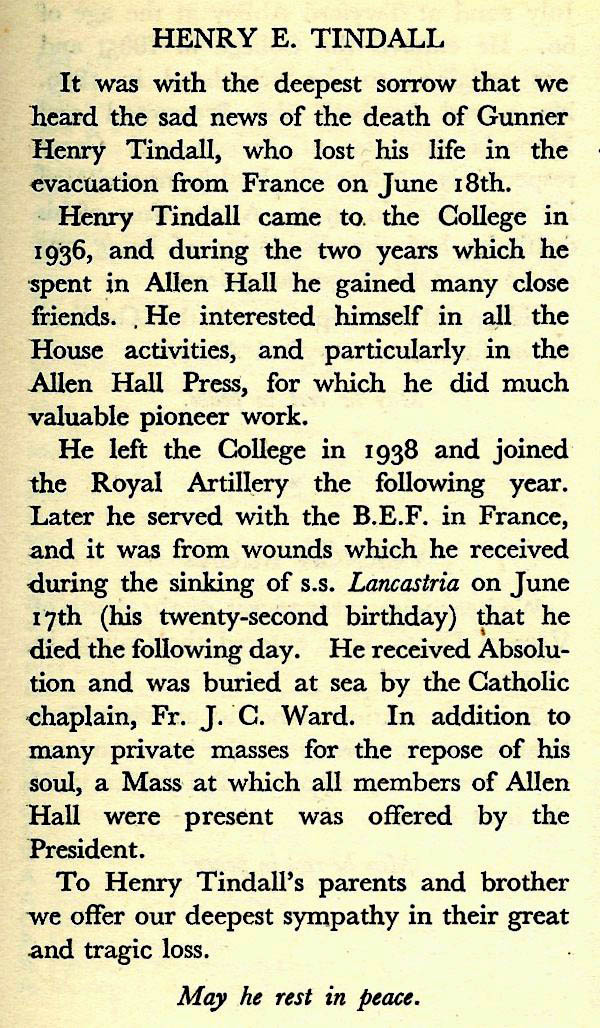

Captain Charles McMenemy had succeeded in reaching a French tug and on it spent the remainder of the evening helping to pull people from the sea as the boat cruised slowly backwards and forwards, finally dropping off the survivors alongside the destroyer Highlander. One survivor he recognised immediately despite the oil which coated the body. Gunner Tindall (left) and the padre had originally gone to the same school, then lost touch with one another. Neither were they to re-establish contact, for the private was very seriously wounded and died that same night."

(Gunner Henry Edgar Tindall (above), age 22 of 53 Heavy Anti-Aircraft Regt. Royal Artillery, service number 1491110 - recorded as dying 18th June from his wounds. - Son of Edgar and Elizabeth Tindall) He is commemorated on the Dunkirk memorial. They buried him at sea shortly after he died on the 18th of June.

The tug must have picked up five or six hundred but it was grisly work with less than an even chance of survival for so many. The toll rose even higher. Drowned, shot choked by oil. McMenemy happened to look down and saw another familiar face in the water. It had been his duty to read so many letters, censoring them for any incautious statements. Sergeant Burke's letters had never presented any problem, but it would be no pleasant task to write to his widow, or call later to see the children.

Finally they are transported to the Oronsay from the highlander:

Late that evening, Padre Charles McMenemy came aboard. One of the first people to speak to him on deck was the Irishman who, several hours ago, had dived into the sea full kit. The man was still completely dressed and equipped save for his helmet. There was no mistaking that snub nose and caricature of a long upper lip. 'So you made it, Mike?' smiled the padre. 'Good for you'. Then he turned in mock severity. 'But whatever happened to your tin hat?'

'Well now father,' the Irishman responded warmly 'Was like this. It must have fallen into the water when I jumped overboard. Should be in South America by now. But I'll not let it happen again!'

|