|

SHETLAND'S LINK WARTIME TRAGEDY FORGOTTEN BY HISTORY

This story was first published in the Shetland Times in June 2005

Captain Sharp was master of the Lancastria when German bombers sank her in June 1940, with the heaviest loss of life in British maritime history. Mark Hirst picks up the remarkable story of this naval officer with family links to Shetland.

Captain Rudolph Sharp was five feet eleven inches tall, stout in build and looked older than his age. He came from a seagoing family from Shetland, with a rich experience and tradition of the seas. His grandfather and uncle had both served with the Cunard Line. Some said their first impressions of the man apparently revealed a serious nature to his personality and that his expression took on a certain weariness when faced with unexpected aggravation. A typical Shetlander older family members said. Yet all that was before Sharp became destined to be associated with the two of the most infamous and heavy naval losses of World War 2.

He had certainly served an interesting naval career and had held various positions on such luxury liners as the Mauretania, Olympic, Franconia, Lusitania and even the Queen Mary but in March 1940 he rejoined the Lancastria, a 16,242 ton Cunard liner which had been in service with Cunard's White Star line since 1922. Lancastria, like the Queen Mary, had been built on the River Clyde the heart of global shipbuilding.

Britain had been at war since the previous September. Lancastria, had been on a cruise in the Bahamas at the outbreak of war when orders from the Admiralty in London arrived and she was immediately requisitioned as a troop transport and sent to New York to be fitted out. Her standard Cunard red, white and black paint was replaced with battleship grey and a 4" gun mounted on the stern deck where normally wealthy cruise passengers took a dip in the pool.

One of Lancastria’s first missions in the war was to transport troops from Greenock to Norway as part of the attempt to stem the Nazi invasion of that country. The then First Lord of the Admiralty, Winston Churchill, had been behind the plan to supply British troops to Norway, but the plan was doomed from the outset and the Norway campaign ended in failure. Less than a month after disembarking troops, Lancastria was sent back to pick them up after the Germans overran the country.

As they returned to Namsos to pick up the men, Harry Grattidge, the Chief Officer of the Lancastria, and Sharp’s number 2, said: "the men were dirty and depressed, most of them without rifles".

The Norway campaign had been a disaster in its own right, yet Churchill escaped blame despite being the man ultimately responsible for the Norweigan plan. Just weeks later he became Prime Minister.

As they sailed south, passing Shetland, to Orkney to secretly off-load the men from the Norway campaign, Sharp looked out from the bridge. In the distance he could just make out the rugged features of the islands and pondered what his life may have held if his family had remained there.

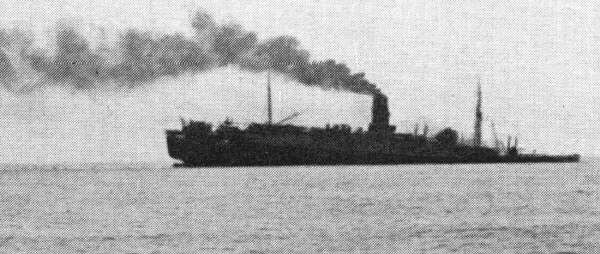

Lancastria sails out of Shetland in a cruise prior to the war

By the 14th of June Lancastria was back in her homeport of Liverpool for a major refit. The men of the Lancastria needed an overhaul as much as their ship. However no sooner had the men been given leave than Cunard’s head office issued orders for all men to return to the ship and prepare to set sail that evening. Captain Sharp in his interview to the shipping causalities section later that month clinically noted:

"We left Liverpool on the 14th of June at 17.00, arriving at Plymouth on the 15th. We left Plymouth at midnight and arrived at the Charpentier Sea Roads, Saint Nazaire at 04.00 on the 17th of June".

Soon after two Royal Navy officers on orders from the Admiralty boarded Lancastria and instructed Captain Sharp to load as many men as possible, "without regard to the limits laid down by international law".

It would prove to be a fateful decision for the thousands of souls who later boarded the ship. Chief Officer Grattidge, who later went on to become Commodore of the Cunard Line looked at the two fresh faced naval officers and with bitter memories of Norway in his mind said: "Is this another capitulation?" "

Don’t even mention that word" came the terse response.

Earlier a local French pilot skipper had warned Captain Sharp that to be anchored in the Charpentier Roads during daylight was like "putting your head in the noose". But what choice did Sharp truly have?

As Captain Sharp stood on the bridge and watched the endless stream of vessels taking troops of the British Expeditionary Force out to Lancastria he quickly glanced upwards. Every now and then he could see aircraft high up in the sky, the sun catching their wings in a fine flash of scintillating light, "like dragonflies" Sharp thought.

Finally an attack came, but the target appeared to be another liner, the Two funnelled Oronsay. According to Sharp’s log the Oronsay was hit at 13:48 and her bridge section blown away. Miraculously none of her crew were killed in this attack although she began to list heavily to port.

Immediately after the attack and with Lancastria’s decks heaving with soldiers and refugees Sharp discussed the options with Grattidge. Should they leave now or wait until they had proper escort. Two Royal Navy destroyers were moving about at this time, HMS Havelock and HMS Highlander. Sharp ordered that one of them should be signalled to see if they could offer escort for the Lancastria back to Plymouth. U-boats were known to be lurking in the Bay of Biscay and Sharp knew that there was not enough lifeboats or lifejackets for all those aboard and so Sharp did not feel secure in setting sail alone.

A signal man repeatedly signalled one of the nearby destroyers, but was met with only a discreet silence. "I think" said Sharp at last, "that we’ll do better to wait for the Oronsay and go together." and looking at Grattidge said: "What do you think?" Grattidge agreed. Soon after the sky seemed to clear of aircraft and both Grattidge and Sharp headed for their cabins, both exhausted and drained. Sleep did not come easy and both men remained restless.

At 3.45 pm on the afternoon of 17th June 1940 the sirens on the harbour at St. Nazaire sounded. Flying at over 250 mph a stream of German bombers, Junkers 88, from the German squadron Kampfgeschweder I/30 swarmed overhead. This unit was a specialised in anti-shipping.

On the 13th of November 1939 this very same unit became the first bombers to target British soil when they attacked the flying boat base at Sullom Voe. All four bombs dropped harmlessly into an open field, but Shetland humour being as it is someone placed a dead rabbit (which had actually been bought from a local butcher) in one of the bomb craters. The national press were quick to exploit the opportunity and used the "slain" bunny for propaganda purposes.

As one of the Junkers swooped low over the water aiming at Lancastria’s stern it suddenly released four 500kg bombs. Grattidge later described the sound of the falling bombs as the "longest and most fearful silence I have ever heard."

By the time Grattidge had reached the bridge Captain Sharp was already there.

"By heaven, sir, this is really bad"

Sharp shouted to one of the other officers on the bridge "How many down

No. 2 hold?"

"About 800 RAF, Sir. Why?"

Sharp replied staring out over the blown hatch cover, below the bridge "I think that first one struck there and blew away their exist. My god, look at those flames."

All four bombs had struck the Lancas tria and caused utter devast ation.

It quickly became clear Lancastria was doomed. "Clear away the life boats". Sharp said suddenly realising the scale of the developing situation. Grattidge grabbed a megaphone and bellowed: "Clear away the boats now, your attention please, clear away the boats now."

Each lifeboat held about 100 people. Slowly, some of these started to be lowered into the sea, as Lancastria quivered and shaked beneath the feet of Captain Sharp. He knew they did not have long. Oil from Lancastria ruptured fuel tanks were spreading quickly around the sinking liner. Finally, after several chaotic minutes that witnessed the full range of human emotion, Sharp turned to Grattidge and said: "It’s time now, Harry. I’m going to swim for the after-end." Grattidge looked at his watch: 4.08pm. Knowing Sharp was a poor swimmer he made him take the only lifebelt on the bridge. "Good luck, Sir". They both stepped off the bridge and into the oil-soaked sea 9 miles from the harbour at St. Nazaire.

Thousands of men now clambered onto the turning hulk as Lancastria headed for the bottom. Some started to sing, in defiance to the still swooping enemy aircraft, "Roll out the barrel". As they sang German aircraft flying over the wreck started machine gunning men in the water and on the turning hull. One seem to drop an incendiary in attempt to light the 1400 tons of fuel oil which was escaping from Lancastria. It was a truly macabre spectacle.

Only a handful of Lancastria's lifeboats could be lowered in time. Some lay in the water upturned, with dozens of men desperately trying to clamber on top of them. All were black, covered in oil and exhausted. One officer standing on what was once the side of Lancastria calmly pulled out his revolver and shot the man in front of him, before turning the gun on himself, his lifeless body tumbling down the side of the ship and into the water. As Lancastria slowly began to disappear the sound of singing was replaced by the screams and shouts of thousands in the water, most without lifebelts and with no hope of rescue. Some, in sheer panic began to attack those survivors who had lifebelts. It was a desperate and horrific sight which changed the lives of all those who witnessed it and survived that day.

After hours in the water and witnessing many men dying in front of him, Sharp was picked up and finally transferred back to Plymouth. Later that week he met with Grattidge in a pub in Liverpool and prepared the official report of how Lancastria had gone to her death. "Latitude 47.09. Longitude 2.20" Sharp said as he wrote quickly in his notebook. He would never forget that position. It marked the graves of more than 4000 men, women and children. He was still weak and light headed with oil poisoning from Lancastria’s ruptured tanks which he had swallowed whilst in the sea..

Sharp had lost more people under his command than any other naval Captain in British history. A tragedy worse than the combined loss of life in both the Titanic and Lusitania disasters. But for Sharp the war was not over.

After a short period of rest he was back as master of a number of merchant vessels. By 1942 he was Master of the Laconia as she sailed south off the Ivory Coast with 1800 Italian PoWs on board. Suddenly the 20,000 ton vessel was hit by a single torpedo, one of two, fired from U-156. Laconia stopped dead in the water and the submarine surfaced. Eyewitness accounts say that as the last lifeboat was lowered away Captain Sharp stood on the deck, smoking a cigarette, the glow from the end visible after the survivors entered the water. Other reports say that once he realised the ship was doomed he could not face losing another vessel and so locked himself in his cabin and awaited his fate. He went down with the Laconia along with 1600 other victims.

Afterward a number of U-boats descended on the scene to pick up survivors. As they sailed to the nearest port with survivors towed behind in lifeboats the U-Boats came under attack from US fighter bombers and suffered casualties. In response Admiral Dornitz, the German naval commander issued the infamous "Laconia Order" which forbid German naval vessels from assisting in the rescue of survivors. After Lancastria, the sinking of the Laconia became the 2nd worst naval loss of life in the war.

On learning of the sinking of Lancastria Winston Churchill banned all news from reaching the British public, fearing it would demoralise them yet further.

On the 17th of June 2005 the remaining survivors of Lancastria sailed out to the wreck site for the last time and to remember the forgotten dead of the Lancastria and a Captain who lived and died for the sea.

|