Kampf Geschweder 30

The Luftwaffe Unit responsible for sinking the Lancastria

The flight of Junkers 88 (A-4) bombers of One Kampf Geschweder 30 unit had already left their base in Amsterdam-Schiphol aerodrome, in occupied Holland on their way to attack targets of opportunity from the retreating Allied armies. The unit, known as the Umbrella Geschweder because of their distinctive crest, specialised in anti-shipping operations.

I / KG 30 had already seen action early in September 1939 where it attacked targets in Scotland, specifically the Orkney Islands which were regarded by the British as a major strategic naval base in the North Atlantic and home to the High Seas Fleet. Three of KG30's aircraft were lost within a month due to the heavy defences in around the natural harbour at Scapa Flow. KG30 also suffered the first Luftwaffe loss of the war after one of their JU88s was shot down during an attack on the Forth Rail Bridge, north of Edinburgh.

Meanwhile the bombers headed South West on that warm summers day in June 1940. As they flew over France they could see Paris in the distance out their port windows. Five days later Adolf Hitler would visit Paris, touring the near empty streets, before ending up at the Eiffel Tower.

It is unclear whether this flight of bombers had been notified by earlier air patrols that two large liners were embarking troops in the Carpenter Sea Roads leading into St. Nazaire. Earlier that day another troop transport had arrived around eight in the morning. Like the Lancastria it too began loading men and refugees. The 20,000 ton Orient liner, the Oronsay, had been built on the Clyde in 1925. Now the vessel lay anchored less than half a mile from the Lancastria. At 1.48pm it came under attack.

A stick of four bombs were dropped around the ship. One of them made a direct hit on the ship's bridge, wrecking the wheelhouse and destroying the navigational charts. Debris fragments shot out towards the Lancastria.

Men aboard Lancastria witnessed the attack and some decided that things might be healthier topside and so progressed towards the stairs, against orders. Like many soldiers many men had grabbed lifejackets believing that they would make good pillows for the long trip to the English coast. Some men from 663 company, Royal Engineers had managed to get themselves towards the fore deck of the ship next to the main hatches of numbers one and two holds.

The Bridge of the Oronsay was smashed and broken following the attack. The crew quickly got to work setting up the auxiliary steering. She was taking on water but the pumps were managing to cope. The explosion had destroyed the Oronsay's Chart Room and it would take all of the Captain's guile and skill to get the liner back to Plymouth. With the ship's compass gone he eventually used an old hand compass to navigate home.

The Luftwaffe had concentrated its efforts on attacking the Oronsay, possibly because it had two funnels and not one single funnel like the Lancastria. Grattidge was quietly relieved that in comparison the Oronsay looked the more juicer of the two shipping targets to the German bombers. That relief would be short-lived.

At approximately 3.45 in the afternoon the sirens at the harbour in St. Nazaire sounded the alarm once more. On board Lancastria the crew blew whistles on the decks and below the electric gongs warned of the approaching enemy aircraft. The patchy cloud which had appeared overhead gave some cover to the attackers. Grattidge had just retired to his cabin. He was exhausted and desperate to sleep, but sleep would not come.

Above two bombers were beginning their attack, swooping down from around 3,000 feet and coming in at low-level. The first of the Junkers 88s passed diagonally from Port to Starboard about 150 feet in front of Lancastria's bow and heading once again for the Oronsay.

Every available gun was firing away at it. Travelling at around 270 mph it made a very difficult target. It had a maximum bomb load of 6,614lb (3000kg). Its crew of five were tightly packed together knowing that in an instant they could be shot down by the barrage of metal which was being fired at them. The bombs were released missing both ships and sending huge flumes of water and vapour hundreds of feet into the sky.

The second bomber, the aircraft which was to sink the Lancastria, began its attack from approximately a South Westerly direction. Many eyes were still on the first aircraft as it banked steeply away and climbed out of danger. As the second Junkers 88 lined itself up for the attack the pilot and bombardier must have seen the decks were packed tight with troops. Thick black smoke from Lancastria's funnel was trailing back some distance over her stern. Captain Sharp had given the order for the liner to be fully steamed and ready to go as soon as they received the signal.

Bren gunners were firing continually as the aircraft swung down over the stern. Some on board could see the Nazi insignia on the underbelly and then click. Four 500-kg bombs were released almost simultaneously. The Junkers had passed completely overhead by the time the bombs struck the Lancastria. One appeared to (but did not) go down the single funnel. Two of the bombs struck separately in Number 3 and Number 2 holds blowing the steel and wooden plated hatch covers, which were half the size of a tennis court, completely off. The fourth bomb landed in the water on the Port side but ruptured the plates, letting in many thousands of gallons of seawater.

The Junkers of Kampf Geschweder I/30 swooped away unsure whether they had done enough to sink the liner. A second wave of bombers was on its way, loaded with incendiary bombs. It is unclear whether these aircraft were from the same unit. What is clear now is that as the 16,000-ton ship began keeling over onto its portside the aircraft which had dropped the fatal bombs came sweeping in again strafing survivors, and soon to become victims, of the sinking troopship.

The aircraft's gunner and engineer would have been behind the two MG81 machine guns firing 7.92mm rounds into the Lancastria. They would have known that the ship was finished, but continued firing. When the second wave of bombers approached loaded with incendiaries they immediately attempted to light the oil which was spewing out of Lancastria's ruptured oil-fuel tanks. Lancastria was carrying around 1,400 tons of oil when she was hit; this was now posing a great risk to those survivors who were now struggling in the sea and in the few lifeboats which had managed to get away.

Thankfully most of the incendiaries which were dropped did not ignite the free-flowing oil. Because of the exceptionally low altitude which the bombers were coming in, the fuses had not been set properly to allow the bombs to be fully primed by the time they hit the water. It was not a mistake which the technicians who had armed the more conventional, high-explosive bombs which had hit the Lancastria had made.

Nonetheless the psychological affect on those survivors who witnessed this attack and who had been so ruthlessly targeted was severe and one which they would never forget nor forgive. Finally the skies fell silent and the Germans did not return again until night.

The Carpenter Sea Roads lay still. Thick oil, wreckage, dead fish, broken men and thousands of dead and dying troops floated on the surface.

|

Satellite image of Loire estuary

The loss of life was overwhelming and ultimately the final death toll will never be fully known. What is known is that at least 36% of all BEF troops killed in action between September 1939 and June 1940 were lost during the sinking of the Lancastria. The death toll was at least twice that of the entire losses inflicted upon the BEF during the ten-day evacuation of Dunkirk.

According to German air station reports prepared by the Luftwaffe Operations Staff, 8 transports and one tanker were sunk that day. Four transports had been damaged. An estimated 91,000 tons of shipping had been sunk and 68,000 tons damaged.

None of the ships were named, but one report claimed to have sunk a troop ship estimated at 30,000 tons and described as a "fully loaded transport". This, presumably, was the Lancastria.

That night Lord "Haw Haw" broadcast news that the Lancastria had been sunk. He had done this several times before and although it is unlikely that he would have known it, this time he was right.

Update:

There has continued to be much debate over exactly which unit sank Lancastria. Recently author Brian Crabb inferred that II/KG30 sank Lancastria in his book "The Forgotten Tragedy". Interestingly however he wrote that as Junkers from II/KG30 approached and circled the Loire estuary where Lancastria was located a Junkers 88 "from another Gruppe of KG30 was shot down". Certainly the Germans did not know that they had sunk Lancastria or air operations records would have reflected this. Is it possible that the KG30 Junkers 88 which Peter Stahl of II/KG30 saw was responsible for the attack on Lancastria?

Many survivors claim that Dornier 17's were responsible or even Heinkel 111s. Some other survivors and authors claim that Junkers 87 Stukas were responsible, although the mode of attack swooping from bow to stern rather than the classical dive bombing technique of the Stuka rule this out, not to mention the fact that Stukas were not operational in the Loire area until the 23rd of June.

What is likely is that the pilot responsible for sinking Lancastria did not survive the war, such were the losses of the Luftwaffe from 1940 onwards.

Update 2

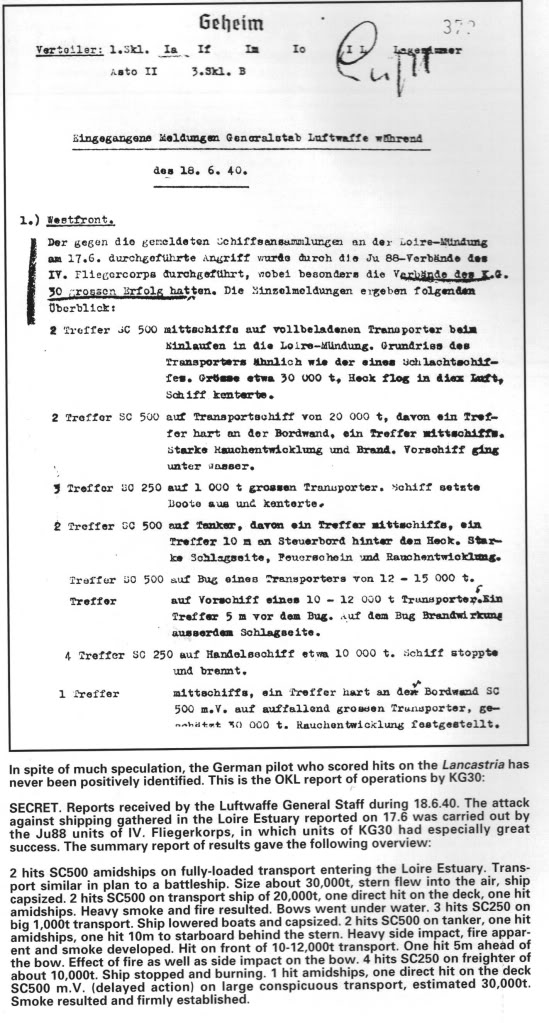

Below is the official German air operations summary for 17th June 1940 related to the action KG30 pilots were involved in. It indicates that KG30, Group IV carried out the attack. The summary also indicates that several of KG30’s pilots claimed to have hit and sunk shipping in the Loire that day, but clearly they are referring to the Lancastria, the only vessel in the vicinity at that time to have been sunk. It demonstrates that the accuracy of reports from pilots in action was subject to much variation and very much open to question. A translation of this report is noted at the bottom.

|